Burlington Company SiPhox Health Says Do-it-Yourself Home Blood Tests May be Available Next Year

It looks like a Mr. Coffee machine, but a new device from Burlington-based SiPhox Health runs on blood.

Insert a few drops, and the machine will use laser light and microchips to identify dozens of medical biomarkers related to a variety of illnesses, ranging from rheumatoid arthritis to kidney disease. And like the coffee machine, it’s designed to be used at home.

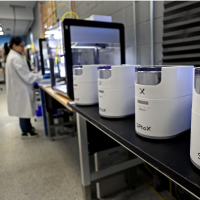

A row of lab analyzers sat atop a counter at SiPhox Health.David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

A row of lab analyzers sat atop a counter at SiPhox Health.David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

Founded five years ago, SiPhox already sells a $150 at-home blood testing kit. Users ship their samples to a remote lab via FedEx, and test results arrive in a week. But that’s just a warmup for the company’s real goal. By 2026, it expects to field a service that’ll let people do the entire process in their bedrooms.

“The real holy grail is to have it done immediately at home, because it cuts the cost by a factor of three,” said SiPhox cofounder Michael Dubrovsky. The SiPhox machine promises results in about an hour, with no need to pay for FedEx shipping. Instead, the results will be transmitted instantly to the patient’s physician via an internet connection. SiPhox won’t sell the machines, only the cartridges that hold the blood and the chemical compounds used in the tests. Each test cartridge will cost between $50 and $75, and Dubrovsky expects that a typical customer will run a test four to 12 times each year, depending on the state of their health.

If all this sounds familiar, you’re probably thinking of Theranos, the notorious medical testing company that claimed to have built a machine capable of running hundreds of medical tests using a single drop of blood. The Theranos story ended with bankruptcy and prison sentences.

But even a decade later, the capacities of SiPhox’s devices are more modest than those touted by Theranos. Dubrovsky vows that his product works as advertised, and he promises to secure clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration before bringing it to market.

Dubrovsky and his cofounder Diedrik Vermeulen met at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2019. Vermeulen was a research scientist in silicon photonics — microchips driven by light instead of electricity — while Dubrovsky was a graduate student in materials science. Neither had a background in medicine. But the chief market for silicon photonics, the telecommunications industry, is already full of well-established players. Meanwhile, they realized that silicon photonics chips could dramatically downsize the bulky, costly optical systems found in today’s blood testing machines.

They founded SiPhox in 2020., and hired a team of biotech experts, including people who’d worked at Harvard’s Wyss Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital. The company has raised $32 million in venture money from investors, including Y Combinator, Intel Capital, and Khosla Ventures. SiPhox quickly developed its mail-in blood test using conventional technology and began collecting data for use in developing an inexpensive photonic blood testing system.

A decade ago, Theranos gained major investments from companies like Walgreens and Walmart by falsely promising accurate tests for hundreds of medical conditions. But Dubrovsky said SiPhox doesn’t even attempt many of these tests, such as blood cell counts, because it’s not practical with SiPhox technology.

Instead, SiPhox focuses on immunoassay tests, which mix the blood with antibodies that react to specific proteins and hormones in the blood. The resulting reaction can be used to measure the quantities of these blood chemicals. A typical laboratory machine can perform hundreds of tests per hour, but they can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

SiPhox’s photonic chips are each about the size of two grains of rice side by side. Each home blood test comes in a plastic cartridge that contains one such chip.

Each chip has an array of tiny sensors, and each sensor is treated with a protein that reacts to a particular biomarker in the blood. The chips shown off in a recent visit to the company had 14 such sensors; the company will seek FDA clearance for a version that will contain 45 tests.

Along with the chip, the plastic cartridge is a receptacle for holding a few drops of the user’s blood, extracted almost painlessly from the person’s shoulder. The cartridge also contains a supply of several chemical compounds. As each test is performed, the correct chemical is mixed with blood and flushed over the surface of the chip.

“It’s like a chemistry lab in there,” Dubrovsky said.

The SiPhox machine pumps the liquids over the chip, while aiming a laser at each sensor on the chip, one by one. The light that reaches the sensor reveals the amount of each biomarker present in the user’s blood. The results will be transmitted instantly to the patient’s physician. The user pulls the test cartridge and throws it away.

John P.A. Ioannidis, professor of medicine at Stanford University and one of the first scientists to raise the alarm about Theranos, said that routine blood tests are a waste of time and money for most people. “Testing, like any other medical procedures, requires some reason,” he said.

But he added that the SiPhox system could be good news for people with chronic diseases, who need regular testing. “It’s good to have technology that’s easier and faster,” said Ioannides. “There’s some merit in allowing people to get a bit more control of their life.”

Dubrovsky agrees that over-testing is a bad idea, but only up to a point. “This is also the argument used against full-body MRIs, which save lives all the time by finding early cancers,” he said. “There is such a thing as testing too much, but for the average American, we are nowhere close to that threshold."

Most customers for the company’s mail-in tests receive them four times a year. Dubrovsky thinks that’s also the sweet spot for his in-home testing system. It’s enough to monitor existing illnesses and spot new ones, and enough to make the system a success.

Article via The Boston Globe

-

Hiawatha Bray Globe Reporter

- February 10, 2025

- Send Email